Euxenia 1

‘Euxenia’ is a compound word in ancient Greek. The root of the primary word is ‘xenos’ or guest; ‘xenia’ is the solemn and sacred code of hospitality one must afford them. Failure to adhere to this code was an affront to Zeus, the most powerful member of the pantheon. The word ‘xenia’ refers overtly to this generosity, voluntary or otherwise, but just under the surface is the thought that the guest has the potential to be a threat: our modern word ‘xenophobia’ includes some of this unease. More Information

The prefix ‘eu-‘ means simply ‘good’, but here again the full significance is not derived by accepting the meaning at face value. In the linguistic world of the ancient Greeks, it was often applied apotropaically, in other words with full awareness that the subject in reality embodied the exact opposite of the stated meaning, in this case ‘good’. Names were sometimes given in this way in the hope that the characteristics of the place or being would change to fit the name. They usually didn’t.

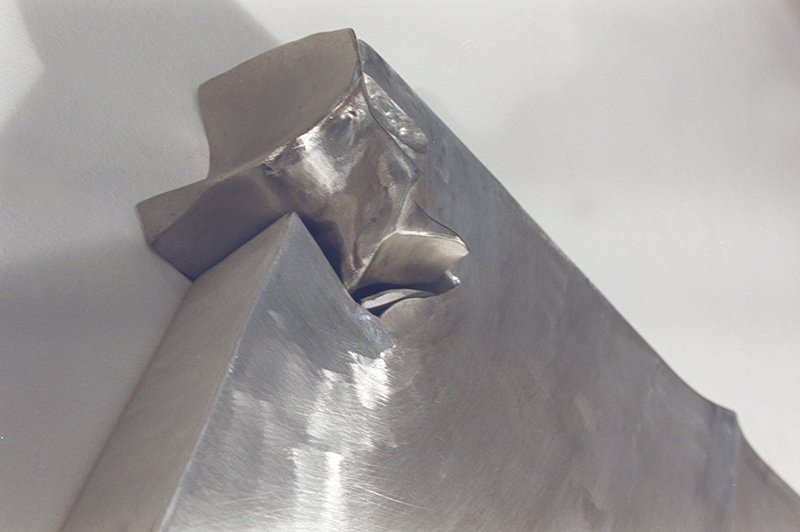

The glaciological genesis for these pieces is the majestic phenomenon of frozen-in icebergs. Their captivity is sometimes reinforced by being aground as well. These obviously were free floating at one time, and are destined to be so again, at which point they will resume their perambulations. Eventually, their travels will lead them to locations where they will melt away forever. Their imprisonment is also their security and longevity.

Similar contradictions apply to the sea ice and its interactions with its ‘guests’. While powerful enough to imprison even immense icebergs sufficiently large to be considered ice islands, it has a short life span, and responds to local changes on a much shorter cycle that the bergs, usually disappearing after one season, or a few seasons at most. In many cases, the relative movement between the captive bergs and the sea ice creates leads and other openings that attracts wildlife; the scouring of the sea floor by ice is an important natural mechanism. The foreign body can be a force of enrichment, not just a passive guest or an invader.

It is hoped the the layering of internal contradictions implied here will suggest and illustrate our ill-defined role of being simultaneously natural and non-natural, of simultaneously ‘belonging’ and being an invader. Operating as we thus do at an conceptually uneasy ‘no man’s land’, any self-understanding useful in its potential effects on our future will perforce involve insight into these conundrums.